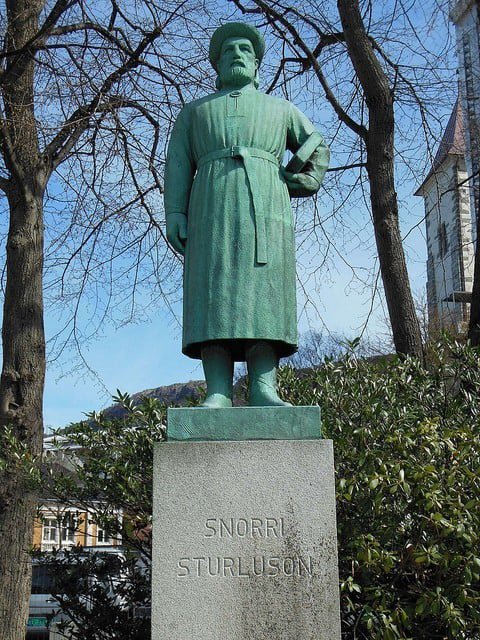

Book Review: "Song of the Vikings -- Snorri & the Making of the Norse Myths" and NorsePlay on the priceless "Prose Edda".

Whether you're Ásatrú, Heathen, or a Norse Studies academic, the important questions most of us who pick up Nancy Marie Brown's Song Of The Vikings: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths are actually looking for answers about are why Snorri Sturluson wrote the Prose Edda, how compromised by the conversion are its contents, and beyond those, is there a divine manifestation in its writing?

Before we approach those answers, this 2012 CE work first uses sources & then extrapolations to determine who Snorri was. In terms of direct accounts, the Sturlunga Saga shows Snorri's role in the time directly before Iceland cedes its independence to Norway. Beyond this, Brown's technique of assembling the character of Snorri is somewhat of a deconstruction of his literary output. Brown infers that since Odin had certain pronounced qualities (i.e. wisdom, guile, leadership, ladies' man who fathers it up) that Snorri in turn had these qualities.

This line of thinking would imply that since Tolkien wrote Aragorn, that he in turn possessed those Ranger-esque tendencies (big maybe, though he did serve in WW1's The Battle of the Somme, so sort-of?). Yet, despite the possible fallacy of this, Brown's sighting seems to hit the target in the way Brown outlines Snorri's life decisions & interactions with others by using this literary-to-real-life parallel. Brown's suppositions feel right (and yes academics, that's not evidence, it's following intuition). They are reasoned & reasonable, and until Snorri's secret diary shows up from its hiding spot under a rock next to his hot tub in Reykholt we have this bio as the best thing going. And better than that, it makes for a creative & stylistically fun read as Brown alternates between telling the myths and Snorri's life as he quests to become jarl of Iceland.

So first, let's examine the odd question of Christian contamination in the Prose Edda: Brown surmises that even though Snorri had access to many Christian Latin works at the school he attended at Oddi, that influence "did not stick" as his writing doesn't reflect those stories or much of those literary conventions, and she quotes one Prose Edda translator as saying "it would scarcely be possible for a writer trained in Latin grammar and rhetoric to write as Snorri does." (p28-9 [and if you read even deeper in Faulkes' essay The Sources of Skáldskaparmál: Snorri's Intellectual Background {1993 CE}, he goes so far as to posit most of those Latin works were probably not even readily there.])

One weird serpent which eats its own tail is that many "Christian influences" were Heathen in the first place. One specific example Brown mentions is that Snorri's Alfar of light/dark/black gradations more resemble angels from the Christian text Elucidarius (p201), which may have been in his learning library at Oddi, but others note that its author Honorius Augustodunensis was actually influenced by English folklore, which probably has Scandinavian & Germanic origins. Plus the translator of Elucidarius into Old Icelandic (c. ~1200 CE, though this would've been quite late in Snorri's education, so perhaps he elected to read it soon after) may have in turn used Alfar-ish terms to then describe the angels. And so it all goes back to the Norse Lore anyhow, if only by degrees of the conversion's remove & displacement.

In looking at the more general transmission & infusion of ideas, the church borrowed from the Ancient Roman, Mithraic, and other Indo-European rituals, so those same factors & elements of being "compromised" actually comes back around to survive within Christianity itself (and possibly re-emerge in reconstructionist practices).

If we examine how much the Heathen Worldview endures post-conversion within Scandinavian society, then what we have is a hammer-for-cross-necklace swap, the raids of the Viking Age becoming the plundering Crusades of the 11th century, and those sworn thanes of the jarls instead becoming the king's knights. Snorri is Christian in label but still in many respects functionally pre-Christian in terms of how he plays the chieftain/lawspeaker/skald roles, none of which were post-conversion values, but pre-conversion social reputation statuses & secular power goals, all of which is so not practicing the gospel of Christian humility, but more deeding boldly like a Heathen.

Secondly, let's examine why the already biggest Icelandic chieftain Snorri would then bother with writing the Prose Edda: Brown relates that during his tour of Norway, Snorri did act as a literary anthropologist like the folklore collectors the Brothers Grimm or Asbjørnsen & Moe of his day, listening, asking, and recording the Norse Lore as he travelled though different regions of the country. This in part was with the aim of self-aggrandizement, yet one can argue that perhaps all writers share that, but for Snorri it was even more: The big takeaway of this bio was that Snorri wanted to use the well-known cultural capital of Icelandic skaldship with the Norwegian court, but because the king was only 14 (!), Snorri had to write a textbook that would explain why his wordsmithery was so valuable, ergo the Prose Edda, so he could then be seen as an asset and then try to fulfill his ambition to become both their court skald & Norway's jarl of Iceland.

Snorri was a politician and power broker, so it stands to reason he had to lie about trying to settle a legal kerfuffle back home over some slain Norwegians in order to play the game, but the literary by-product I don't believe was a lie or a mere tool any more than storytellers tell stories with different facets of emphases depending on their intended audience, which in this case was specifically teen King Hákon Hákonarson and his co-regent/father-in-law Jarl Skúli.

Yet this status-inducing literary payload of poetic technique & Norse Lore was never delivered. After Snorri's assassination (actually by agents of King Hákon since Snorri was seen to side with the more appreciative Skúli, whose rebellion ended with the would-be usurper's death), his writings were either gathered by nephew Saga-Sturla or younger nephew Olaf White-Poet, and barely survived in a handful of subsequent manuscript copies.

|

| [The possible flowchart of sources for the Prose Edda into the seven manuscripts it was compiled from.] |

Ultimately the politically practical reason Snorri writes the Prose Edda for doesn't happen, and of only three wrong decisions this highly intelligent, ambitious, and powerful man makes in his life, it is his attempt at foreign networking that weaves his eventual doom.

Thirdly, the nonsecular or paranormal question that could be asked about the Prose Edda is if there's a divine manifestation in its writing, which NorsePlay is asking in light of (but beyond the biographical scope of) Brown's work.

Brown relates that centuries later when Scandinavian monarchs realized the value of medieval records in re-establishing their kingdoms' heritage & credentials were Iceland's manuscripts then proactively sought out and collected.

Icelandic priest Arngrímur Jónsson gathers Snorri's Prose Edda & Heimskringla with others, and in 1609 CE publishes the Crymogæa (Greek for "Ice Land"), a history of Iceland, which then re-introduces Europe to the Norse Gods, the Sagas, and the Runes, which re-popularizes the Norse Lore.

Snorri's aforementioned payload, like a long-dormant then activated bomb, culturally explodes in the late 1600s CE, when the Prose Edda finds printed distribution outside of Iceland, continuing to stoke public interest in Norse Mythology by providing its most coherent & direct source to this day.

Within the scale of its purpose, Snorri's reasons for writing the Prose Edda included the literary preservation of the Norse Lore and its poetic forms, not only for what was already written, but as a how-to structure for its use in the future. In this long-term fulfillment we have to acknowledge as a work the Prose Edda punches way, way, way above its weight class as a mere collection of fantastical stories, list of literary references, and poet's manual. While Snorri's Prose Edda is clearly the work of one talented mortal man and isn't a sacred text or meant to be a fossilized scripture-like dogmatic religious account of the Gods, it is this amazing snapshot or single preserved filmstrip of how those stories were told at the time he wrote them down. They were different before, they were different after, and they will thence become different in our own future.

When the Norse Lore relates the detail that the God of Poetry Bragi's tongue is inscribed with runes that mean inspiration, we are being handed the skaldic means by which to be licensed as storytellers. The Norse Lore is open source code, and the Prose Edda gives us agency to NorsePlay. You're supposed to embellish, fill-in, and make it the best narrative it can be to the best of your creative individual abilities. You're allowed to. Part of that point is to honor the Gods by winning the room, and that in itself is performing a ritual. The stories of the Lore come from an endless oral tradition, they play a game of telephone from telling to telling, gathering details and expanding truths with their polyvalent beauty. They are deep & enduring & resonant, and so adaptable, from their original fireside-in-the-hall audience roots to someone using a videogame controller to electronically engage with them today. It is that survival and continued greater renaissance of the Norse Lore that is in itself a persistent divine manifestation extending from the Prose Edda. Like Odin sacrificing himself on the World Tree to obtain the magic runes to write down & preserve ideas for all time, the Prose Edda finds its equally magical function as a divine vessel.

Quite beyond Brown's assessment & Snorri's political or literary intentions, the Prose Edda's a time capsule that the Gods will forever live inside of, and a set of metaliterary construction tools that allows them to emerge & manifest in the telling so we can once again recognize, evoke, and be with them.

“And now, if you have anything more to ask, I can’t think how you can manage it, for I’ve never heard anyone tell more of the story of the world. Make what use of it you can.”

~ Snorri Sturluson

[spoken by Hárr (One-Eyed) in Gylfaginning §53, Prose Edda]

Guillermo Maytorena IV knew there was something special in the Norse Lore when he picked up a copy of the d'Aulaires' Norse Gods and Giants at age seven. Since then he's been fascinated by the truthful potency of Norse Mythology, passionately read & studied, embraced Ásatrú, launched the Map of Midgard project, and spearheaded the neologism/brand NorsePlay. If you have employment/opportunities in investigative mythology, field research, or product development to offer, do contact him.

Comments

Post a Comment